The people who wrote an ordinance banning the aerial spraying of pesticides in western Oregon last year aren’t professional environmental advocates. Their group, Lincoln County Community Rights, has no letterhead, business cards, or paid staff. Its handful of core members includes the owner of a small business that installs solar panels, a semi-retired Spanish translator, an organic farmer who raises llamas, and a self-described caretaker and Navajo-trained weaver.

And yet this decidedly homespun group of part-time, volunteer, novice activists managed a rare feat: They didn’t just stop the spraying of pesticides that had been released from airplanes and helicopters in this rural county for decades. They also scared the hell out of the companies that make them, according to internal documents from CropLife America, the national pesticide trade group. Although some of the world’s biggest companies poured money into a stealth campaign to stop the ordinance, and even though the Lincoln activists had no experience running political campaigns, the locals still won.

The Lincoln County aerial spray ban, which passed in May 2017, is just one of 155 local measures that restrict pesticides. Communities around the country — including Dubuque, Iowa; Reno, Nevada; Spokane, Washington; and Santa Fe, New Mexico — have instituted protections that go beyond the basic limits set by federal law. Some are aimed at specific pesticides, such as glyphosate, others list a few; while still others ban the chemicals altogether. In the three decades after the first local pesticide restriction was passed in 1970 in Maine, the bans came in a slow trickle. These days, they are coming in a flood, with towns and counties passing more of these measures in the past six years than they did in the 40 before that, according to data from the advocacy group Beyond Pesticides.

The uptick in local legislation is a testament to public concerns about the chemicals used in gardening, farming, and timber production, and reflect a growing frustration with federal inaction. In recent years, scientific research on pesticides has shown credible links between pesticides and cancer, endocrine disruption, respiratory illnesses and miscarriage, and children’s health problems, including neurobehavioral and motor deficits. As scientists have been documenting these chemicals’ harms, juries have also increasingly been recognizing them.

But federal regulation has lagged behind both the research and public outrage. Notably, the Environmental Protection Agency has allowed glyphosate, the active ingredient in RoundUp, to remain in use despite considerable evidence linking it to cancer. Under Donald Trump, the EPA also reversed a planned ban of chlorpyrifos, a pesticide linked to neurodevelopmental problems in children. Frustrated by the lack of federal action, many people have turned to their towns and counties, only to find that they have been hamstrung by state laws forbidding local limits on pesticides.

In 43 states, laws prevent cities, towns, and counties from passing restrictions on pesticide use on private land that go beyond federal law. A provision in the Farm Bill now before Congress would extend that restriction to the entire country and could potentially roll back existing local laws. The House version of the bill that passed in June and is now being reconciled with the Senate version included a section that prevents “a political subdivision of a State” from regulating pesticides.

The measure is one of several “anti-environmental provisions” in the bill “that threaten public health,” according to a letter from 107 House members. The Republican-backed attempt to clamp down on local governments also flies in the face of the party’s rhetoric, according to Scott Faber, vice president of governmental affairs at the Environmental Working Group.

“Hypocrisy is not a strong enough word for Republicans working to block local public health ordinances designed to protect children,” said Faber. “It’s a party that more or less exists to empower local government to make decisions.”

While the industry is hoping to tighten its already fierce grip on localities through federal law, it’s also waging a stealth campaign against local “brushfires,” as CropLife America refers to the local attempts to restrict and ban pesticides. In Lincoln County and elsewhere, the national trade group is quietly putting its vast resources into fighting local activists through opposition research, monitoring their social media, and trying to stop opposition to pesticides from spreading to other communities.

“Tier 1 Concerns”

While the campaign for the aerial pesticide ban in Lincoln County was being run on the cheap, opposition to the measure, which was ultimately voted on by fewer than 14,000 Lincoln County residents, came from some of the world’s biggest companies. CropLife America, the industry group, which reported more than $16 million in revenue in 2015 and represents and collects dues from the major pesticide manufacturers, including Monsanto, Syngenta, Dow AgroSciences LLC, and DuPont Crop Protection, ranked state and local issues as the top of its list of “tier 1 concerns” for both 2017 and 2018, according to internal documents obtained by The Intercept that pinpointed Oregon as ground zero for the fight.

Teaming up with Paradigm Communications, a division of the U.K.-based public relations firm Porter Novelli, CropLife America launched a national campaign to provide “intense levels of support where the most dire battles are,” according to a state activities memo prepared for the CropLife America 2017 annual meeting, showing that Paradigm had spent 44 percent of its budget for this effort in just two Oregon counties: Lincoln and Lane, its neighbor to the south.

The industry group’s work to fight the local campaigns in Oregon included holding two “meetings to organize Protect Family [sic] Frames and Forests” — a group that was central to opposition to the ban in Lincoln County; creating and testing messages; conducting a “brainstorm session for potential activates”; setting up meetings with key players in the county; conducting “Sentiment Research,” holding trainings in media, social media, and public speaking; creating direct mailers, a logo, and a website; doing “social media research” on voters; creating a “Facebook strategy,” which included a Facebook page and a “secret Facebook Page”; writing a script for door knocking; creating talking points; writing and editing 15 letters to the editor; and “auditing strategies” of three groups involved with the local laws — including the Oregon-based environmental group Beyond Toxics and the Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund, which the CropLife America documents referred to as “CEDF.”

While the national industry group paid for all this, its name never appeared on the materials or was referenced in the local fight, which was instead framed as being led by local farmers.

John Trinkle flies a crop duster to spray a field of tomatoes September 26, 2001 in Tracy, CA. chemical agents. Image: Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

The industry has also been waging surreptitious campaigns outside of Oregon. In Boulder, Colorado, which voted last year to phase out neonicotinoid pesticides and GMOs on public land, the CropLife America and Paradigm Communications team worked behind the scenes to push back the date that the phaseout would take effect and conducted “adversary research,” according to the CropLife document.

CropLife America and Paradigm Communications also conducted adversary research in Washington state, where they spent another 29 percent of their budget. In Washington, their tactics also included building “out geo-focused Facebook Groups to establish internal communications” and holding a four-day training for nearly 50 people that included sessions on “how to interact” and “how to read body language.”

Volunteering to Fight Pesticides

Lincoln County Community Rights doesn’t have an office, so the group often holds its meetings in members’ homes, which are scattered throughout the county’s more than 1,000 square miles of forest and coastline. On a recent Friday, it was Debra Fant’s turn to host. A retired nurse whose house near the coast is surrounded by tall spruce, hemlock, and fir trees, Fant made quiche for the occasion.

As her fellow advocates sat eating around her dining room table in flip-flops and T-shirts and their dogs nosed around for crumbs on the floor, Fant thumbed through records of the group’s expenses. There weren’t many. Almost all of their work is done for free. Fant herself volunteers about 20 hours a week, emailing and making calls as well as managing the group’s social media. John Colman-Pinning, a farmer who grows organic vegetables and raises a small herd of llamas, does research for the group in his spare time. And Rio Davidson, who owns a solar panel company, designed and maintains the group’s website and Facebook page.

Barbara Davis, an intensive care nurse, considered herself apolitical before she began volunteering for the group a few years back. Davis moved to the area from Reno, which had felt overdeveloped and far from nature. Lincoln County, which is 90 percent forest and has no big cities, seemed the perfect antidote. “We came here in 2004 thinking it was clean and green,” said Davis. Learning about the spraying changed her feelings about her home.

The Forest Service banned aerial spraying in national forests in 1984, in part due to a fierce battle over the issue in Lincoln County. But timber companies still regularly apply herbicides and fungicides from airplanes onto private land here, Davis discovered. The chemicals are used to eliminate plants that compete with trees after clearcutting, a practice used in the timber industry to uniformly remove all the trees in an area. Among the chemicals they spray are 2,4-D and glyphosate, respectively labeled possible and probable carcinogens by the World Health Organization, and atrazine, an endocrine disruptor. Aerial application of the chemicals is cheaper than employing people to apply it from the ground or pull weeds by hand. But it allows the chemicals to drift over large areas, affecting water supplies, and the health of people and animals.

- “I would start knocking on doors in my neighborhood and they’d start telling me about their cancer stories.”

Davis began reading — and worrying — about the health effects of pesticides. Although she had previously shied away from difficult political conversations, she began driving her old Honda around the county with a hand-scrawled “public health or corporate wealth” sign in its back window to promote the ordinance. Davis met with little resistance when she explained that it would reduce pesticide exposure, as well as the health problems she feared it was causing around the county.

Judging from the conversations she struck up as she distributed leaflets, many of her fellow Lincoln County residents shared her concern. “I would start knocking on doors in my neighborhood and they’d start telling me about their cancer stories,” Davis said. “I had two neighbors down the road who died of brain cancer. Nobody can prove cause and effect, but I connected it to the spraying — and a lot of other people did, too.”

The group decided to highlight stories of some of the people who had suffered from pesticide exposure. One of its mailings featured Loren Wand, a local farmer and landscaper whose wife, Debra, had been sprayed by pesticides from a helicopter in her 20s. “Prior to getting sprayed, she looked like Ali MacGraw,” Wand told me recently. Directly afterward, Debra developed respiratory problems that gradually worsened. Her health steadily deteriorated and she died of cancer at age 44. “I have no question the spraying was related,” said Wand, who doesn’t use pesticides in his farming or landscaping businesses.

But while the members of Lincoln County Community Rights were talking about the human consequences of pesticide use, their opponents were pushing out their own message. Three local business owners who rely on pesticides argued that the ordinance threatened their families’ legacy by taking “away essential tools to prevent the spread of invasive species.” Others argued that the ban would increase farmers’ expenses. And Oregonians for Food & Shelter, a statewide organization, felt that “counties really lack the expertise” to regulate pesticides, as Scott Dahlman, the group’s policy director, told me. “It’s why we have state agencies that handle that.”

The ban’s opponents didn’t tackle the health questions, focusing instead on one of the law’s provisions that spelled out citizens’ rights to use “direct action” to enforce the ordinance if necessary.

Who’s Afraid of Direct Democracy?

The group remains split on the wisdom of including the direct action provision, which a county judge ultimately decided was the one part of the ordinance that should not be enforced. Maria Sause, the part-time translator who helped write the aerial spray ban, felt the language clarifying people’s rights to enforce the law corrected an existing power imbalance. “We’re being accused of being eco-terrorists,” Sause said. “But the way the laws are right now, the corporations have priority over the citizens’ right to defend their own health and safety. That’s terrorism.”

For his part, Davidson thinks the group shouldn’t have included the phrasing that gave citizens the right to enforce the ordinance because it resulted in their being tarred as dangerous extremists. “At least we could have put in nonviolent direct action,” he said of the language, which he noted was added in the last week before the measure was submitted.

In any case, much of the opposition to the ban focused on its direct action provision, arguing that it showed that people who wanted to limit pesticides were dangerous radicals. The opposition group created by CropLife America — and given the environmentally friendly-sounding name Protect Family Farms and Forests — produced videos warning that the ordinance would allow “anyone to take the law into their own hands with no legal consequences.” On Facebook, the group warned about the possibility of “trespassing, vandalism, destruction of property, and even bodily harm,” should the law take effect.

- “They were trolling us pretty hard. Any time we had a radio interview, they would come out with a press release two hours later bashing us.”

While the activists had no experience crafting campaigns and very little money to pay for outside help, Protect Family Farms and Forests seemed to have ample resources to effectively push out their message.

“They were trolling us pretty hard. Any time we had a radio interview, they would come out with a press release two hours later bashing us,” said Davidson. “Every single website you go to would have their ads running. They paid for advertising everywhere. Radio, TV, internet.” And while both sides had dueling Facebook pages, opponents of the ban also bought ads on the site. “Even when you were on our page, you’d see ads for theirs,” said Davidson.

Protect Family Farms and Forests also mailed fliers about the dangers of the ordinance to everyone in the county, including Colman-Pinning, the llama farmer. Although they were designed to raise opposition to the ban, Colman-Pinning saw the glossy mailers describing the ban as an assault on family farms as a call to action. “It was really smarmy stuff,” said Colman-Pinning. “Karl Rovian.” And it was voluminous. “They sent out eight direct mails to every one of ours.”

Unreported Campaign Contributions or TK

In a meeting of CropLife America’s board of directors held last September in Laguna Nigel, California, Paradigm Communications presented its activities in Oregon as a success. A briefing document for the meeting listed their campaign in Lincoln County as one of five major accomplishments of 2017.

Poll numbers listed in the state activities memo (which at first incorrectly places the effort in Lane County) showed that opponents of the spray ban were initially lagging by 26 points. “Through a combination of messaging and on the ground activates we were able to close that gap to zero,” the memo notes. “The methods used to fight the battle in Lincoln County showed that with intense training and local involvement; we can move large portions of the voting population.”

Yet in Lincoln County, where the spray ban is now in effect, the fight over the ordinance can also be seen as an illustration of the exact opposite point: that a small, committed band of people can restrict the use of pesticides even when their resources are dwarfed by those of their opponents. The ordinance passed by 61 votes in May of last year despite the contributions of powerful groups, including the Fertilizer Institute, the Koch-supported Oregon Forest Industries Council, more than a dozen local farm bureaus, DuPont, and Oregonians for Food and Shelter — a group created in 1980 to “do battle with activists seeking an initiative to ban the aerial application of forest herbicides,” according to an archived page of its website.

Exactly how much was spent fighting the local ban is unclear. According to state records, supporters of the ordinance, who created a separate group called Citizens for a Healthy County in order to be able to lobby, received $21,600 in cash and in-kind contributions, most of them small gifts from individuals, including several members of Lincoln County Community Rights. Meanwhile, the group formed to lobby against the ban, the Coalition to Defeat 21-177, received more than $475,000 in contributions, much of that from farm bureaus and industry groups.

- “Oregon has a robust online reporting system. [...] Contributions to campaigns are supposed to be reported.”

But the total amount of contributions to the Coalition to Defeat 21-177, which represents 22 times the contributions to the ban’s proponents and about $34 spent for every voter, doesn’t reflect any expenditures or services provided by CropLife America. The group’s internal documents show that it spent heavily to fight the ban in Lincoln County. The documents didn’t specify the total spent on its joint effort with Paradigm Communications, but they do show that CropLife America expected to spend more than $10 million on staff, consultants, and vendors in 2017 and clearly considered its work in Oregon a top priority. Yet none of the group’s spending on the ban was recorded in the Oregon Secretary of State’s database. State law requires public reporting of all contributions to campaigns over $750, including those from out-of-state organizations.

“I believe it’s a violation of both the spirit and letter of the law,” said Kate Titus, executive director of Common Cause Oregon, when alerted to CropLife America’s unreported expenditures on the Lincoln County ordinance. The state’s campaign finance law requires the reporting of anything of value given to influence the outcome of an election on a measure — whether it’s cash or services — to an online system run by the Oregon Secretary of State. “The intent of that is to make sure voters know who’s behind all the money in elections. Contributions to campaigns are supposed to be reported,” said Titus.

Dan Meek, a public interest attorney based in Portland, Oregon, agreed that CropLife America’s failure to report its spending to fight the ordinance was a violation of state law. “Every contribution has to be reported,” said Meek after being told of the spending. Meek, who began representing Community Rights Lane County last month, said that “everything the national group did is an illegal contribution” — whether the group was acting in conjunction with the organized attempt to defeat the ban or independently. “If they are found to be doing this willfully, it is also a felony.”

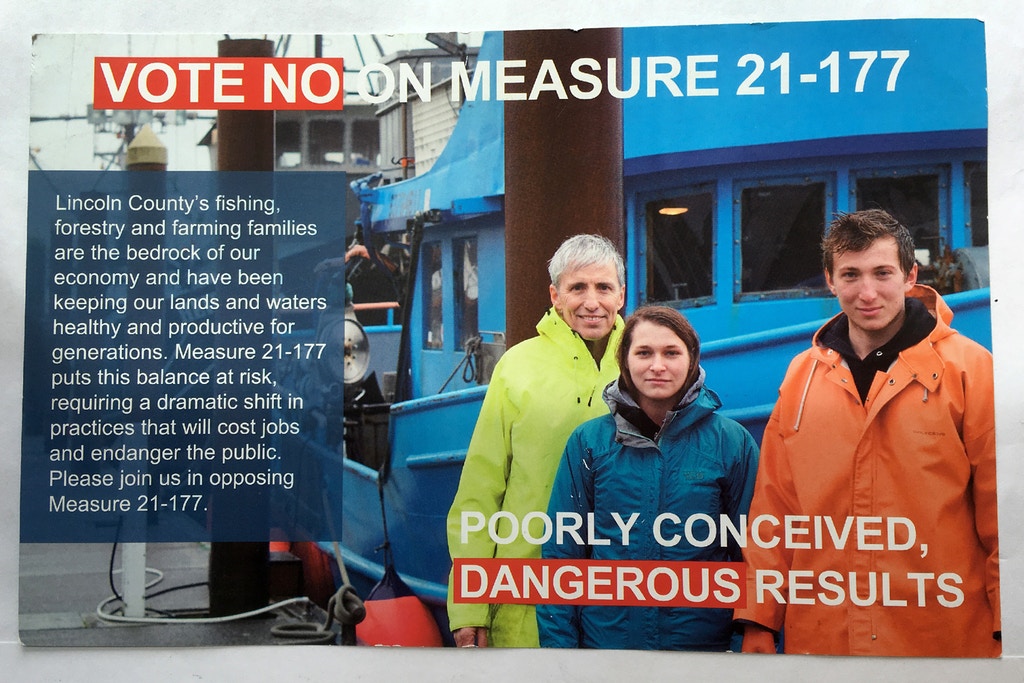

One of the flyers mailed out by Protect Family Farms and Forests to residents of Lincoln County.Image: Courtesy of Barbara Davis

CropLife America did not return repeated phone calls or respond to emailed questions about its campaign. Porter Novelli also declined to comment for this story or answer specific question about its involvement with CropLife America.

Communities Fight Back

Much of the opposition to pesticides in recent years has focused on enforcing existing laws, some of which establish buffer zones around schools, parks, and other areas in which pesticides cannot be used. But the groups in Oregon — along with others that have sprung up around the country — have taken another tack: changing the laws.

Like the ordinance in Lincoln County, a similar proposal in neighboring Lane County didn’t just specify that aerial spraying would be outlawed, it asserted people’s “inherent and inalienable right of local community self-government.” Both measures were inspired by the Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund, which views the aerial spraying of pesticides as violations of citizens’ basic rights to clean air, water, and soil.

CropLife America has taken a particular interest in the group, which was co-founded by Thomas Linzey and has distinguished itself by arguing not just for the rights of people, but the rights of nature itself. “That sounds hippie-dippy, but the fact is that pesticide applications affect ecosystems, rivers, and forests,” Linzey said when contacted by phone. The Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund was founded in 1995 and started off doing traditional legal work, such as enforcing statutes like the Clean Water Act and Clear Air Act. But the group switched to the community rights approach in 2001, out of frustration with their lack of progress. Since then, Linzey said, it helped pass more than 200 local ordinances in 10 states focusing on longwall coal mining, fracking, and large-scale water withdrawals, among other issues.

In Lane County, which reaches from the Pacific to the Cascade Mountains, the environmental group’s help has yet to yield any victories. An amendment to the Lane County charter that would ban aerial spraying of pesticides has been in the works for at least three years, but has yet to make it to a vote. Supporters of the ban gathered some 30,000 signatures, but a local judge ruled that the proposal couldn’t be added to the ballot after a timber industry supporter sued the county.

Michelle Holman, who has been fighting against pesticide use in Lane County for years, moved to rural Oregon to be closer to nature. But soon after she arrived in the late 1970s, Holman discovered that many local women were having health problems. Just among her own friends, she knew of four who had had miscarriages, two who had stillbirths, and one whose baby died shortly after being born. Holman herself wound up having 10 miscarriages.

“Nobody knows unequivocally why these things happen,” she said. But she came to focus on the pesticides that were sprayed from planes and helicopters in the area. And her gut sense that pesticides played a role in her repeated losses was bolstered by ample evidence linking pesticides with miscarriage.

Holman joined the board of Beyond Toxics, an Oregon group that was working on pesticides among other issues. “We did all the traditional activism — protests, calling agency people, writing letters, having agency people come here, going to corporate headquarters. But we were always told the same thing: This stuff has been tested and it’s legal.”

After Holman went to a presentation on community rights, she became convinced that only way to win the fight against pesticides was to change the laws — and helped found Community Rights Lane County. “I don’t think the planet has time for this incremental shit,” she said. “We need to ban the stuff.”

Unfortunately for Holman and the growing number of people now focusing on changing the laws that determine local control of pesticides, the companies that make these chemicals have already had the same thought. In 1991, after the Supreme Court ruled a town in Wisconsin could pass a ban on pesticide spraying that was more restrictive than the federal pesticide law, it became clear that communities around the country had the legal right to pass their own limits on pesticide use.

“We were really happy about the Supreme Court decision,” said Jay Feldman, executive director of Beyond Pesticides, an organization that formed that year to promote non-chemical pest management alternatives and help rid the world of toxic pesticides. But soon after the ruling, the industry launched a state-by-state campaign to pass laws that prevented other local pesticide limits.

Today, 43 states have some form of pesticide pre-emption law. Twenty-nine, including Oregon, have state laws that specifically prevent localities from adopting restrictions on pesticides that are stricter than the federal law. And 14 have a more limited form of pre-emption, in which a state commissioner or board manages pesticides — an option that Feldman says is “like giving the fox the henhouse.”

Implied Preemption

But even in states that don’t have laws specifically outlawing local restrictions, pesticide makers have sometimes succeeded in fighting them. In Hawaii, one of seven states without pre-emption laws, pesticides have become a huge health and environmental issue. Kauai, the fourth-largest Hawaiian island, which is a testing ground for several major pesticide manufacturers, has been particularly hard-hit. Dow, BASF, DuPont, and Syngenta sprayed 17 times more restricted-use insecticides per acre on cornfields there than on those in the U.S. mainland, according to a 2015 report from the Center for Food Safety. A recent study by the Hawaii Department of Agriculture found pesticides in 31 of 32 water samples on Kauai and Oahu, the island to its south. And a substantial number of honey samples on the island were also recently found to contain glyphosate.

In 2013, when he was a member of the Kauai County Council, Gary Hooser proposed a bill to limit the spraying of highly toxic pesticides near schools, homes, day care centers, hospitals, and waterways. The fight over the bill was bruising. “They painted people like me as being crazy activists, anti-science,” said Hooser.

“I’ve been doing politics and government for 20 years, and I’ve never worked with any industry as intense and thuggish as the chemical companies,” said Hooser. “They filled the room full of their workers and told the world that Gary Hooser, and this bill was going to cost them their jobs.”

Despite the efforts, the Kauai measure passed. But Syngenta, BASF, and Agrigenics, a company affiliated with Dow AgroSciences, sued on the grounds that Kauai’s law was pre-empted by state law. And even though Hawaii has no pre-emption law, a federal appeals court judge agreed with the companies in 2016 and struck down the measure.

- “What’s so disheartening is that it took just one judge to undo years of activism by so many groups.”

In Montgomery County, Maryland, another local pesticide ban was overturned last year despite the fact that the state has no pre-emption law. The Healthy Lawns Act would have prohibited the use of certain pesticides on lawns starting in January of this year. But six local lawn care companies, along with the lobbying arm of CropLife America called Responsible Industry for a Sound Environment, or RISE, successfully sued the county. The county has since appealed the ruling to a Maryland Court of Special Appeals, which heard the case this week and is expected to rule on it soon.

“RISE was basically the lead,” said Ling Tan, a mother who began working on a local law to restrict pesticides after she realized that toxic lawn products were being sprayed while her two daughters, who both have asthma, were outside playing. Tan, who first asked her homeowner’s association and the Maryland State Department of Agriculture for help with the issue, has been working on the ban with other parents since 2013.

“What’s so disheartening is that it took just one judge to undo years of activism by so many groups,” said Tan.

A court may soon reverse the hard-fought win in Lincoln County, too. On June 6, 2017, one day after the ban on spraying from planes and helicopters took effect, a lawsuit was filed to declare it invalid on the grounds that Oregon state law pre-empted the ordinance. The named plaintiff, Rex Capri, who owns timberland in the county, was later joined in the suit by Wakefield Farms LLC, another local landowner. Both have aerially sprayed their timber trees with pesticides in the past and want to continue doing so.The complaint filed in their suit doesn’t mention CropLife America. But a report from the trade group’s legal department notes that “CLA is closely working with Oregonians for Food and Shelter (OFS) and Oregon Forest Industries Council (OFIC) in a legal challenge to” the Lincoln County ban.

Legal wrangling also continues in Lane County, where the authors of their spray ban are still fighting to bring it before the people of the country for a vote. Rob Dickinson and Michelle Holman, members of the all-volunteer group that has been working on the charter amendment for years, acknowledge that the county may not succeed in banning aerial spraying of pesticides — and that, if they do, the ban may then be overturned by the court.

Either way, they feel the fight is worth having. “When the black students sat down at that lunch counter, it wasn’t a failure that they didn’t get served lunch,” said Dickinson. “The only way we fail is if we stop fighting.”

As much as it is fueled by a deep desire to get the chemicals out of their air and water, the activists say their fight is about democracy. “We’re the freaking people. We have inalienable rights,” said Holman. As long as they keep fighting, there’s at least a chance they’ll be able to exercise those rights to rid their communities of pesticides.

“It’s definitely a David and Goliath situation,” said Holman. “But sometimes David wins.”

This article was reported in partnership with The Investigative Fund at The Nation Institute, now known as Type Investigations.