Gloria Castillo and her three children hated almost everything about living in their 21-story Bronx public housing building in the St. Mary’s Park Houses. The locks on their lobby doors were often broken, and the security cameras too, permitting a free flow of unauthorized visitors into the building. In her nearly 20 years there, the certified nurse’s aide and Salvadoran immigrant had filed dozens of requests for service for everything from the broken locks to a bedbug infestation that she and her family suffered twice to heaping trash outside her windows. She’d reported drug deals and drug abuse, attended community public safety meetings, and meticulously kept receipts, correspondence and pictures, all with the aim of one day getting her family out. Hoping that among the New York City Housing Authority’s (NYCHA) 325 other developments, she might somehow land in a better one, she had applied to move to a new building and was put on a wait-list in August 2013.

For months, she anxiously awaited her turn. When she became witness to a shooting in November 2012, her resolve to get out of St. Mary’s Houses became even stronger.

That brisk Sunday morning, around 10:30 am, Castillo was watching TV in her bedroom when she heard shots and ran to her window. Gunfire was a common sound, ringing out at least once a month, more often in the summer months. As she always did, Castillo got up and checked on her children. All were fine. But then, looking out at the building’s entrance below, Castillo saw an armed man running away. Shortly afterward, she heard screams for help from a person who appeared to be staggering up the staircase, and the thud of a body collapsing in the hallway in front of her second-floor door.

Recognizing the cries as her elderly neighbor’s, she rushed out to help. Against the pleas of her three young children, she opened her door, the only person on the floor to do so. There, her 67-year-old neighbor lay bleeding. Grabbing rubber gloves and her daughter’s much-loved “Dora the Explorer” towel, she worked quickly, removing layers of clothing and administering pressure while her son called 911.

Thankfully, the wounded neighbor lived. And the alleged shooter was arrested. But in the aftermath of the shooting, Castillo’s building wasn’t simply full of nuisances like bedbugs and broken locks — it was full of potential enemies. The alleged shooter and his family and friends lived in St. Mary’s Houses too, and Castillo would now be called upon to incriminate him. When she eventually testified at his trial, the shooter saw her face. Both of the 911 calls that she made were also played, allowing him and his associates to hear not only what she saw that day, but where she and her children lived, even her phone number.

Earning only about $15,000 per year limited Castillo’s ability to move. So, around the time of her June 18, 2014 testimony, Castillo asked the Bronx District Attorney’s Office to help her apply for an emergency transfer from St. Mary’s Park Houses. Designed to relocate residents who have witnessed or experienced certain crimes, NYCHA’s emergency transfer program offered Castillo what she thought would be her fastest route to a safer building. But there began what Castillo has since described as a “nightmare.”

An ever-present threat

While violent crime has been steadily declining in New York City for the past couple decades, progress against crime in NYCHA has halted. After falling every fiscal year from 1999 to 2010, crime in NYCHA began rising again in FY 2011, and has returned to mid-1990s figures, according to a City Limits analysis of NYCHA data in more than two decades of annual reports. Nearly the same number of major felony incidents occurred in NYCHA in fiscal year 2016 as occurred there in fiscal year 1995: 5,205 incidents versus 5,266, respectively.

In February 2017, experts found that more than 33 percent of New York City shootings happen on or within 500 feet of NYCHA developments, and nearly a quarter of all reported New York City rapes happened within 500 feet or on a NYCHA campus.

That’s true “even though at best, or at most, public housing residents represent 10 percent of New York City’s population,” says Greg “Fritz” Umbach, assistant professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice and author of The Last Neighborhood Cops: The Rise and Fall of Community Policing in New York’s Public Housing. “Statistically, you’re much more at risk of rape in public housing than you are elsewhere,” Umbach, who also works with NYCHA and the NYPD as a public safety consultant, tells City Limits.

After suffering from violence, thousands of NYCHA residents who have witnessed or experienced crime in their developments in the past 10 years have been transferred by NYCHA to a new development under the agency’s unique emergency transfer program. According to NYCHA data, more than 7,500 residents were approved for transfer between 2007 and 2015. In 2015 alone, 946 applications were approved for emergency transfer.

But a year-long City Limits investigation, which included interviews with dozens of NYCHA tenants, social-service providers, city officials, experts on NYCHA crime, and housing and legal advocates experienced with the program, as well as a review of almost a decade of emergency transfer program data, has found that many of the families who rely on NYCHA’s emergency transfer program are not getting the help they need.

A way out, for some

Administered by NYCHA’s Family Services department for nearly 30 years, the emergency transfer program is designed to help six categories of people — victims of child sexual violence, victims of domestic violence, victims of traumatic incidents and domestic violence witnesses, as well as other intimidated victims and witnesses of crime — move to a new NYCHA development after violent incidents in their current one.

NYCHA is one of a few large U.S. public housing authorities to offer this kind of program to residents who witness or experience crime. While housing authorities in San Francisco, Chicago, Boston, Baltimore, Philadelphia and Los Angeles have similar programs, NYCHA is the only one nationwide that offers applicants additional help through partnerships with local social-service providers. With city rents climbing, there is a severe lack of apartments available to the the average NYCHA household, which earns $24,336. Most cannot afford to move after a crisis without the transfer program.

But for decades, many applicants who had proof that they had experienced crime were being denied transfers. Until mid-June, NYCHA required tenants applying under the category “intimidated victim” to prove, using police reports and other documentation, that they were victimized not only once, but twice within a one-year period, and in a “non-random” manner at the hands of the “same abuser or associate,” internal NYCHA management manuals and program forms obtained by City Limits show. Sometimes NYCHA showed applicants with one incident leniency and approved their transfer requests, advocates who have years of experience working with safety transfer applicants say. But without this proof, many transfer applicants were denied, these advocates contend. NYCHA denied more than half of the emergency transfer requests it received from applicants who reported being crime victims in 2015, a City Limits analysis of NYCHA data shows.

Those who are approved for transfer often face long wait times to be placed in a new apartment afterward. The wait is on average three to six months, multiple advocates from Safe Horizon and Sanctuary for Families say. Both organizations work with NYCHA to assist program applicants. In July 2017, 256 families who had already been approved for a transfer were on NYCHA’s emergency transfer waiting list, including one family who had been waiting for an emergency transfer since March 2012, data obtained from NYCHA shows.

Families that stay on the waiting list a long time are likely hard to place because they are very large or very small family sizes, which don’t fit the majority of the vacant apartments. A 2015 audit, however, found that NYCHA lacked a rigorous system of monitoring its vacant apartments, and as a result didn’t have a clear sense of where it could place the more than 250,000 families waiting for housing in any of its developments. Hundreds of vacant apartments went unoccupied — some for up to a decade — while crime victims lived in fear. In a written response to the audit, NYCHA agreed to implement a better system of tracking vacancies, but said they didn’t have the funding to expedite repairs on the unoccupied apartments. At present, NYCHA reports that its average turnaround time for vacant apartments hovers at 50 days, well above its 30-day target.

- “Often times, when people turn [transfer offers] down, they turn them down because they're not in a nice area.”

Additionally, many victims are presented with relocation options in areas that are more dangerous than the places they are trying to leave, leading some applicants to decline NYCHA’s offer and stay put, says Maureen Curtis, a vice president at Safe Horizon, one of two nonprofits that works with NYCHA to help crime victims apply for transfer. She’s worked with program applicants for almost 30 years. Once given an offer, a household is allowed an opportunity to refuse it, then receive a second and final offer, which they can also refuse. By the end of that process, less than half of the crime victims approved for emergency transfer actually end up transferring, says Curtis.

“Often times, when people turn [transfer offers] down, they turn them down because they’re not in a nice area,” Curtis says. “And I totally understand that. If I’m fleeing my home because of violence in the home, and now I’m going into an area where maybe there is high crime, I won’t want to go into that area. Some developments you’re reading about in the news, and these are ones that people could be getting apartment offers in.”

Transfer applicants can file an administrative grievance concerning a transfer decision. And, according to Rajiv Jaswa, a staff attorney at the Urban Justice Center, a legal services organization in New York City, those grievances can prompt a review by NYCHA borough management or a hearing. But it is hard to file a grievance or be heard when you do, says Jaswa, who began his career working with NYCHA tenants. Some grievance filings — including those unrelated to emergency transfer — simply get ignored, he says. Some years ago, when he and his colleagues held legal clinics in and around NYCHA developments to help residents file grievances related to a variety of housing issues, Jaswa says he found that many grievances he submitted never received a response, despite follow up.

Even as crime rises in NYCHA, the number of tenants applying for transfer has been decreasing. Requests for emergency transfer have been on a mostly downward trend since at least 2007, declining for all five categories of transfer for which NYCHA supplied data.

A police car exits St. Mary's Park Houses in the South Bronx. The area is served by NYPD Police Service Area (PSA) 7.Image: Ese Olumhense

Jaswa and others blame the dropoff in applications on the overall difficulty they say is associated with filing a successful transfer application. So do some NYCHA tenants. After a family member was shot in the lobby of their building in 2014, one South Bronx family chose not to apply because they worried the process might take too long, with no guarantee they would be placed in a safer location. They saved up and moved into private housing instead. Others say they were misinformed about the program and its requirements by NYCHA staff members, causing unexpected denials. A Brooklyn mother, who needed stitches and a blood transfusion after a former partner slashed her face, neck, and back several times with a meat cleaver — in front of her children — tells City Limits she was denied a transfer because although she applied just before the perpetrator left prison, the incident happened more than a year before she submitted her application, rendering her application invalid because of a rule she says she was not aware of. She eventually moved in with a family member who lived in private housing.

But it’s unclear why the number of applications is dropping now: Jaswa says the emergency transfer process has historically been difficult to navigate for most residents. Outside of the two-incident rule, which Jaswa says posed “really burdensome” documentation requirements on applicants, applications could only be completed in paper form, which sometimes resulted in lost paperwork and delayed processing times, tenants say. At least one tenant who unsuccessfully applied for more than one emergency transfer says that when she went to her building management office to request her file and see what might have been delaying her requests, she was told that her file was lost.

NYCHA makes some changes

In response to our request for a comment, a NYCHA spokesperson declined to be interviewed, but sent a statement defending the emergency transfer program and answering some questions about the program via email.

“We work diligently to accommodate emergency transfers as quickly as possible and are committed to better serving the one in 14 New Yorkers who live at NYCHA,” the agency’s official statement read. “NYCHA’s mission is to provide deeply affordable housing and we strive to make our communities safe and secure for all of our residents.”

- “The Authority is unfortunately limited in its ability to provide broader options to residents.”

Over the years, in the face of criticism, NYCHA has implemented reforms to the program to streamline its handling of emergency transfer requests, including implementing a productivity reporting system to “more effectively manage caseloads and ensure the timely disposition of cases,” the agency said in an annual report earlier this year. NYCHA has also set a 45-day target for informing applicants of transfer request decisions, a goal it generally meets. In October 2014, NYCHA removed the two-incident requirement for some victims of domestic violence requesting transfer, a change that may have been the cause of an increase in approval rates of 26.3 percent for those applicants the following year, from 441 in 2014 to 557 in 2015.

But the spokesperson acknowledged that quickly finding apartments for applicants is a major challenge, and blamed the agency’s low vacancy rate. “Of NYCHA’s 177,000 units, less than one percent is vacant [sic], which is the biggest obstacles [sic] to accommodating transfer applications,” she wrote. “The Authority is unfortunately limited in its ability to provide broader options to residents,” she added.

In addition, the spokesperson wrote in an email, the authority has been working to ensure vacant units are back on the rent roll as soon as possible, and its officials conduct a review of vacant units each month to ensure timely completion of projects. The spokesperson said the agency did not have any data on why emergency transfer requests are falling, even as crime rises.

Citing privacy concerns, NYCHA repeatedly declined City Limits’ requests for data that would illuminate the reasons for denials. Nor did the spokesperson respond when asked to explain why specific applications were denied and whether the two-incident rule was a factor in the historically high rate of emergency transfer denials for scared victims of crime. But the spokesperson said in an email that NYCHA changed this rule in order to comply with a new directive from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, requiring that crime victims seeking emergency transfers no longer be asked to prove that they were the victims of two different criminal incidents.

When asked what residents who have been denied because of the now-defunct two-incident rule can do to appeal the agency’s decision, the spokesperson wrote, “Resident safety is the top priority for NYCHA and the authority does its best to ensure resident needs are accommodated as quickly as possible,” the spokesperson wrote in an email. “If a resident’s emergency transfer request is not approved, the tenant receives information on how to file a grievance.”

The spokesperson did not respond to City Limits’ question about whether an emergency transfer denial had ever been changed to an approval because a grievance was filed.

Since changing the emergency transfer program in June, NYCHA has not updated the information about the program on its website. But in her email, the spokesperson wrote that another change that NYCHA made in mid-June addresses some of the difficulties of finding a safe place to transfer. Now applicants can exclude up to two ZIP codes in locations where they would feel unsafe. And those approved for transfer may now choose to be on a city-wide waiting list, when previously they could only select a particular borough.

In addition, NYCHA tenants can now apply for transfer online, the spokesperson wrote, a move that should help prevent applications from getting lost.

The impact of a wait

Waiting a long time for an emergency transfer is stressful, says Tevina Willis, a former NYCHA liaison and community organizer for the office of City Councilman Antonio Reynoso, and a resident of Red Hook Houses. During outreach events and visits to NYCHA sites within the Brooklyn community where she worked, Willis says, she sometimes heard complaints from residents about the emergency transfer application process.

The program is “bad for a lot of people,” she says. “Let’s start with the word ’emergency’ itself. The definition of emergency in NYCHA is different from what you or I would consider an emergency. When you’re in danger and urgently need help, six months is a long time to be looking over your shoulder and holding your breath.”

The Thomas Jefferson Houses is a NYCHA development in East Harlem, one of 24 NYCHA developments in the neighborhood. Khala Smith moved in there in the mid-1990s and raised seven of her eight children there. In the summer of 2005, her youngest son, then 15, was punched in the face by another man in “Jeff.” When Smith went to her management office seeking an emergency transfer, she was told she needed two criminal incidents to qualify. Later that same day, a Monday, she says, her eldest son was shot five times during an incident in the project. The Smiths, now a family of repeat victims, again asked for an emergency transfer. NYCHA later denied their request, Smith says, telling her the incidents needed to be related to qualify the family as intimidated victims.

After repeated inquiries (and intervention from a social worker) Smith said the family was offered a transfer to a development in Far Rockaway. She considered it, despite the distance from the kids’ schools, until she was told by a policeman she knew that the offer was in a location with worse crime than where she was currently living. She turned it down.

- “I hope I hit the Mega Million and can buy a house, and get the hell up out of Housing.”

She panicked daily, worried that she made the wrong choice. Soon she began tracking crime in Jeff on a calendar on her fridge. When she would see or hear something in the neighborhood from their first floor apartment, she would mark the date with red pen. As time went on, she says, the calendar grew full of red ink, and soon the dates began to bleed together.

The family’s issues continued. Before long, Smith’s youngest son was stabbed twice in the project’s courtyard. She didn’t apply for a transfer then, because, she says, she didn’t think NYCHA would approve her.

A transfer to a safe neighborhood, Smith tells City Limits, might have keep that same son from later being shot in Jefferson Houses in July 2011. While heading to the store with friends, the then 21-year-old was struck by a tempest of bullets — one in his right hand, one in the back, another in the head, grazing his ear, two in the neck, and one in the chest, splitting it open. It is not clear whether that attack was related to the earlier one on that son.

After the incident, her son spent two months in the intensive care unit at Harlem Hospital. One of his lungs had collapsed, and he had needed a blood transfusion. His collarbone was shattered. The bullet that entered his chest was lodged in his rib. Surgeons at Harlem Hospital, who specialize in bullet trauma, feared that removing it would be too risky, so it remains there. The wound behind his right ear refused to clot, and would often open without notice, leaking blood down his neck.

Six years later, Smith’s youngest says he hasn’t felt well since that July evening. His family still holds NYCHA responsible for not relocating them to a safer neighborhood, though his mother is thankful that, unlike others in the project, he is still alive.

“To hell with Housing,” Smith says. “I hope I hit the Mega Million and can buy a house, and get the hell up out of Housing.”

Witness for the prosecution

The first time that the man who was arrested and charged with shooting Castillo’s neighbor went to trial, his case ended in a mistrial, after one of the jurors was seen talking to a member of the defendant’s family. But in 2014, he was convicted of criminal possession of a weapon and attempted assault, and sentenced to a minimum of six years in state prison. As of July 2017, his projected release date is November 2018.

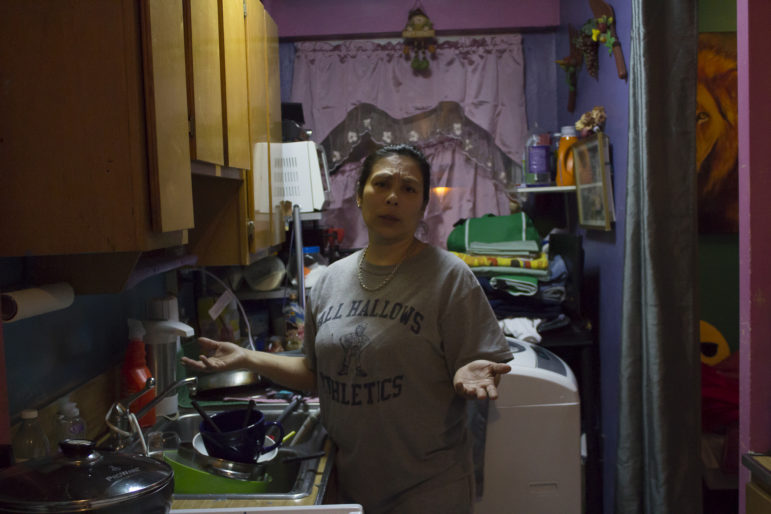

Gloria Castillo in her kitchen.Image: Ese Olumhense

Castillo’s elderly neighbor, who declined to be interviewed for this article, remained in her building. Around the time she testified in the trial the second time, Castillo began her push for an emergency transfer. In support of her application, the Bronx D.A.’s office issued a letter detailing her participation in the criminal case, a key piece of documentation that intimidated witnesses are required to provide.

After denying her twice, saying they hadn’t received a police report from her — despite the fact that she did not need one as an intimidated witness and not a crime victim — NYCHA approved Castillo’s transfer request September 1, 2014, about 60 days after she applied.

Then began her long wait to receive an apartment offer. Despite many follow-ups from Castillo to NYCHA and the D.A.’s office — and appeals from her to politicians, social workers, Safe Horizon, and legal advocates — she waited almost a year and a half before getting an offer.

And that offer was for an apartment in Edenwald Houses, in which the NYPD has a satellite office to help monitor crime. Castillo refused it, fearing that it was too violent and would place her family further at risk. She detailed this and other concerns in a February 2016 letter to the Bronx D.A.’s office. “Edenwald Houses is not one of the safest communities, but in fact it holds one of the highest crime rates in the Bronx,” she wrote. Just two months after Castillo’s letter, 120 individuals from Edenwald and other nearby projects were arrested in a controversial “gang takedown,” then believed to be the largest in New York City history. Prosecutors said alleged gang members there “wreaked havoc on the streets of the Northern Bronx for years, by committing countless acts of violence against rival gang members and innocents alike.” Alleged victims included a 15-year-old child stabbed and “left to die in the street,” and a 92 year-old woman hit by a stray bullet at home.

Castillo was then offered a second choice, in the Boston Secor Houses, not far from Edenwald. Desperate, she went to see it the same day she got the offer, but was dismayed when a housing manager introduced a new requirement, telling her she would need to have one month’s rent and a security deposit in seven days, or she would lose the place. (That’s not how it works, NYCHA told City Limits. The agency requires the applicant to respond to an apartment offer within seven days, but the due date for any fees is only calculated after an applicant accepts the offer.) But she didn’t have the money and she was not allowed to move into the apartment. Her later efforts to find out why hit a dead end, with NYCHA ignoring her repeated requests to review her own application file.

Fearing the shooter would be released soon, Castillo pleaded to the Bronx D.A.’s office, begging for help with her transfer.

“What guaranties (sic) the secure safe stability for the children and I, in the event any retaliation from the criminal incarcerated is intended?” Castillo asked in her February 2016 letter.

Placing blame

Some, including City Councilmember Vanessa Gibson, chair of the City Council’s Committee on Public Safety, feel that residents who ultimately decide not to move into the developments offered them can’t totally blame their situation on the Housing Authority.

“I’m not saying it’s only NYCHA’s fault,” Gibson says. She also blames tenants who choose not to move to the apartments offered after being approved for transfer.

Yet others complain that the emergency transfer program gives applicants only the illusion of choice. There are fairly few low-crime NYCHA developments and they rarely have vacancies.

The agency’s oft-cited failure to promptly repair broken doors as well as hall and entrance lights makes its buildings attractive to criminals. At many sites across NYCHA, as at Castillo’s, entryway doors remain unlocked at all times, locks presumably broken by unregistered, or “off-lease,” tenants who live in the buildings. Lingering scaffolding, under which stealthy criminals can elude view, provides an ideal cover for crime.

Further, NYCHA has allowed violent criminals to live in its buildings, city investigators found recently, even when alerted to their tenancy by police. NYCHA, the audit found, failed to remove for tenants who are “knowingly sheltering dangerous criminal offenders,” bringing just 1 percent of these cases to a hearing for possible eviction in 2016. And by continuing to “allow criminals including gang members, drug traffickers and violent offenders to reside in public housing,” investigators wrote, NYCHA failed to protect the “overwhelming majority of law-abiding public housing residents.” The audit, as well as the process of “permanently excluding” whole families to ensure an individual convicted of a crime is barred from housing, are both controversial. Some legal aid advocates contend that permanent exclusion can have devastating consequences—including homelessness—for the families of people accused of crimes.

Crackdown on crime shows some promise

In the past three years, NYCHA has made strides in reducing violence in the 15 high-crime developments that were selected to participate in a crime-reduction program that Mayor Bill de Blasio announced in 2014. The developments selected for the Mayor’s Action Plan for Safety (MAP) were those that accounted for nearly 20 percent of all violent crime in NYCHA housing — Boulevard, Brownsville, Bushwick, Butler, Castle Hill, Ingersoll, Patterson, Polo Grounds, Queensbridge, Red Hook, St. Nicholas, Stapleton, Tompkins, Van Dyke, and Wagner. The $210.5 million, multi-agency effort provided additional funding for sidewalk lighting and cameras, increased police presence, and more activities for youth and families.

Since 2014, the mayor’s office said, violent crime has decreased 2.2 percent in those developments. Shootings in the MAP 15 are also down nearly 15 percent.

“Crime is down,” says Patricia Hardy-Wiltshire, who supervised the resident watch program at St. Nicholas Houses in Harlem. “And we haven’t had any shootings recently,” adds Hardy-Wiltshire, who has lived in St. Nicholas Houses since 1962. “St. Nick is very safe.”

Others worry that MAP, which only targeted a handful of developments, invested too much money in a program that is too expensive to replicate in the more than 300 NYCHA developments not covered by the initiative, which account for 80 percent of NYCHA crime. Some MAP developments, according to data obtained by City Limits, still produce the most emergency transfer applicants each year. In 2016, Castle Hill, Van Dyke, Polo Grounds, Patterson, and Boulevard Houses saw some of the most requests for transfer.

Asked how the city would expand its public safety goals across all of NYCHA’s developments, de Blasio said in February that the New York City Police Department’s neighborhood policing program, coupled with other “concentrated anti-crime strategies” like those deployed in MAP, comprise a “big sea change” that would reverse many of these trends.

“We have a whole different presence in public housing,” the mayor said in February 2017. “And it’s growing, the neighborhood policing program is growing all the time, it’s getting to more and more precincts,” de Blasio said. “Since overall crime has continued to go down, and generally housing tracks that, I think were very well positioned to have a consistent decrease in crime in public housing, and we’re absolutely going to double down on things like the lighting, and the recreation programs, and all the things we think made a huge difference.”

Since then, additional cameras have been installed in NYCHA developments outside MAP, devices the mayor has called “vital” tools in decreasing crime in these neighborhoods.

But because crime in housing is going up overall, some NYCHA residents and advocates feel that without an exact roadmap for how these initiatives will be rolled out in all NYCHA developments, it is hard to feel included in the agenda that de Blasio, who is running for re-election this year, envisions for New York City.

Still at the scene of the crime

Castillo says she has not received a response to her February 2016 letter to the Bronx D.A.’s office.

“They used me,” Castillo says. “The promise was they were going to transfer me out. I did my part.” The Bronx D.A.’s office did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Castillo still hopes for a transfer, more worried than ever about the safety of her children as crime climbs within NYCHA. She said she has needed counseling herself to cope with the trauma she has experienced in the last few years. Fortunately, associates of the shooter have not targeted or harassed her or her children since the incident, she says, though she and her oldest son have been mugged on separate occasions.

In November 2016, though, one of Castillo’s most-dreaded nightmares manifested, when her youngest son was graphically threatened with rape by a stranger who had gotten in the building, just as the then 13-year-old tried to come home from school, alone. “I know where you live now so you better not tell anyone,” the suspect allegedly told her son, Castillo recalled in a November 17, 2016, letter to Bronx D.A. Darcel Clark.

- “We do not feel safe in this borough, much less in this housing development.”

“This latest ordeal has affected my children and I significantly,” she wrote. “We do not feel safe in this borough, much less in this housing development.”

Though the perpetrator was later arrested and charged with endangering the welfare of a child, he was convicted only on a charge of public exposure and released on time served. Castillo says she was told by building management she would not qualify for transfer under the child sexual victim priority, because, she said she was told, her son wasn’t actually raped, a crime that would have qualified the family for transfer, according to NYCHA’s application for child sexual victim transfers. “Endangering the welfare of a child,” NYCHA rules stipulate, is not one of the crimes that qualifies a family for transfer.

Her son hasn’t been the same since, she says, especially since the perpetrator often frequents the area near her children’s school. The family remains at St. Mary’s Park Houses.

“My heart is broken,” Castillo says. “The system cannot be that screwed up. I don’t believe it.”

Her kids have since given up on moving, Castillo says. “My son told me we should stay here,” she said. “He said ‘At least we know how to dodge the bullets here.'”

This investigation was reported in partnership with The Investigative Fund of the Nation Institute, where Ese Olumhense is an Ida B. Wells Fellow.